A somewhat controversial figure in his own day, Henry David Thoreau rose to his greatest prominence posthumously, in the late nineteenth century, with the publication of his expansive journals. In our day, he remains ranked among the nation’s most interesting and idiosyncratic writers. This list proposes a reading program for “getting” this deep and enigmatic figure.

The popular criticism of Henry David Thoreau has tended to fall into two categories, each the mirror image of the other. From one angle, critics have accused Thoreau of being a misanthrope–so ill-equipped for human community that he had to take his leave of it entirely. As Robert Lewis Stevenson wrote in 1882, “A man who must separate himself from his neighbors’ habits in order to be happy is in much the same case with one who requires to take opium for the same purpose.” Or as Kathryn Shulz put it much more recently, Walden is little more than “cabin porn,” essentially “a fantasy about escaping the entanglements and responsibilities of living among other people.” From the opposing angle, Thoreau has been criticized for staying too close to the civilized world. This species of critique is marked by the tenacious cliché that the hermit of Walden Pond was really just a man-child who had his mother do his laundry.

Thoreau’s critics are wrong across the board, though there are gradations to the wrongness, and some are at least more entertaining than others. (James Russell Lowell’s 1865 hatchet job is excellent, for example, as is Vincent Buranelli’s 1957 “Case Against Thoreau.” By comparison, Shulz’s New Yorker piece, “Pond Scum,” is notable primarily for how much it sucks.) No one is above reproach, and Thoreau had plenty of personal foibles worthy of comment and castigation. But it’s tough to read the man with attention and seriousness and still come away with any such uniformly negative assessment. Those who commit themselves to such positions in print come off looking like bad judges of character.

In any case, there are better approaches at hand. By distancing Thoreau from the political questions, and aligning him instead with a tradition of “virtue ethics” as old as Aristotle, Philip Cafaro demonstrates how Thoreau’s intense dedication to self-cultivation constitutes a politics in itself–or at least a self-conscious model for how to live a thoughtful life with or without close neighbors. It’s a useful example for our day as well, given the variety and the extent of the large social problems that none of us can hope to solve as individuals. Perhaps we should start by cultivating the few cubic feet of flesh over which we are sovereign, or tend the bean field that is ours to till. Done well, such work may develop a healthy sort of citizenship. At minimum, it will yield a healthy and introspective citizen. Probably it will help us minimize the harm we cause, and otherwise help us stay out of debt.

My current project builds on Cafaro’s insights and applies them to a treatment of Walden as an exemplar of American epideictic rhetoric. By identifying the blameable aspects of his neighbors’ lives, and contrasting these with the more intentional and ascetic form of his own, Thoreau diagnoses and critiques the most pressing problems of mid-nineteenth century American life–problems that are exponentially more pressing nearly two centuries later. In this way, and mostly without subtlety, he makes an argument about how the good life should be lived. And while it may come across as condescending or haughty, it is not for those reasons incorrect. Thoreau was a broken vessel, like the rest of us. But he was also a much better writer, and his writing casts a broad net. Everyone should have a decent foundation in Thoreau, and here I identify some books to serve as bricks.

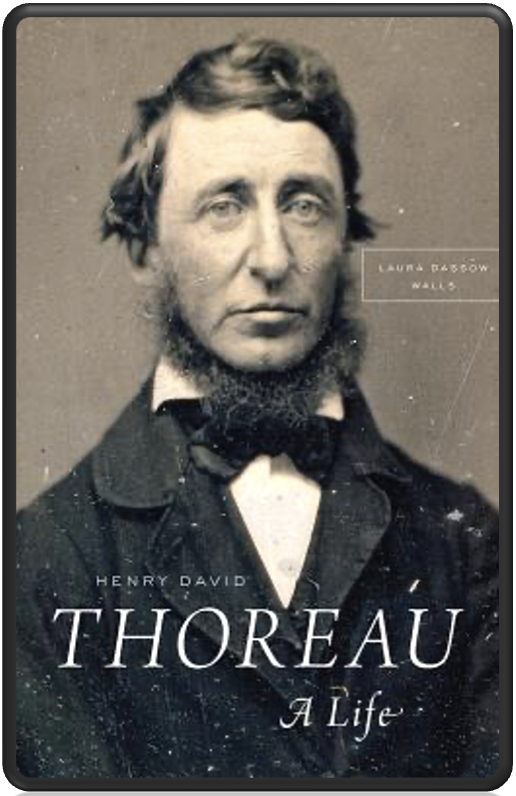

This short list contains thirteen titles, represented as sixteen readings because I’ve split Jeffrey Cramer’s excellent (and annotated) edition of Thoreau’s essays into four parts. That Laura Dassow Walls biography is a master class, paired with one of Robert Richardson’s best. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers is kind of a tough read for those of us not captivated by Thoreau’s poetry or super knowledgeable on the Greek and Roman allusions, but it also has a lot of beautiful description and is notable for the quiet dignity it lends to the author’s relationship with his brother. Walden needs no introduction, of course, and I recommend the four accompanying volumes for context. The Maine Woods and Cape Cod have their moments as well, but ultimately I think it’s fair to say that Thoreau was less compelling as a traveler of New England than as an explorer of himself. I love both of Bob Pepperman Taylor’s books, and I think that Walden Warming offers an appropriate coda to the enterprise–plus another helpful warning for us.

Any time spent here is time well-spent. (Since reading Leonard Neufeldt’s book on Thoreau’s economics, I can’t stop noticing the frequency with which I talk about time, energy, and life being given, spent, wasted, invested, etc.) I began this sort of systematic reading project in the belief that anything worth reading was worth reading well and completely and with resolve. So far the theory holds. As Thoreau put it, “To read well, that is, to read true books in a true spirit, is a noble exercise, and one that will task the reader more than any exercise which the customs of the day esteem. It requires a training such as the athletes underwent, the steady intention almost of the whole life to this object. Books must be read as deliberately and reservedly as they were written.”