In 2023 I read a bunch of books on slavery, Abolitionism, Transcendentalism, the major figures and currents of each, and the ties that bound them to one another. The reading list is included here, along with some reflections on the effort. In the coming year I plan to conclude a pair of other projects-in-progress, focusing on American literature through 1900 and American history through 1917.

The year 1776 regularly serves as a synecdoche for American history–as a small part of the thing that stands in for the whole. For many or most Americans, the association of the Declaration of Independence with July of 1776 has forever established that year as a repository for all American myths, themes, and values, such that it has come to encompass all other years within its red, white, and blue mystique. That is, 1776 is the primary–often the only–historical point of reference that Americans carry close at hand, absorbing so much daylight in their eyes that all subsequent decades are cast in deep, impenetrable shadow. Especially on the American Right, 1776 radically simplifies and clarifies what American history means, quickly converting a textured and perplexing collective memory project into what Van Wyck Brooks once termed “a usable past.” This is why Hillsdale’s foray into public historiography had to be called “The 1776 Project,” and why Tea Party activists so frequently wore tricorne hats. It’s why they called themselves “the Tea Party” in the first place.

To observe that 1776 functions synecdochally is also to engage with every stern and overall-ed gentlemen who has ever stood up at a public meeting to admonish someone for mistakenly calling America a democracy, when it is actually a republic. Though true so far as it goes, this is the sort of claim you can make unequivocally only if your historical awareness extends no further than 1800, or if you simply ignore every new state law passed, every Amendment ratified, every reform movement mustered, and every civil war fought in America between the Constitutional Convention and the present. It has been the obvious tendency of the Amendments, for example, to expand the franchise to ever wider categories of citizen, each redistributing political power more evenly among the population and inviting all to use it well. Though the extensions of voting rights first to Black men, next to all women, and finally to everyone over the age of eighteen receive the marquee treatment, we should also note that non-wealthy white men like those now so fond of this quip were largely denied a seat at the political table in America’s most self-consciously republican decades. Up til and during the gradual, state-by-state repeal of property qualifications for voting starting in the 1790s, the Early Republic was administered explicitly by the elites. It’s hard to imagine that this is the sepia past imagined by the “forgotten men and women” of this latest “silent majority.” It would not explain why Donald Trump hung a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the White House.

But anyway these matters are on my mind now because I recently completed a second pass through American history from the Revolution to the Civil War, focusing this time on Abolitionism and Transcendentalism, specifically. There are fifty very good books on this list, and reading them together has given me a lot to process. One obvious take-away is that some of the nineteenth century’s best and brightest devoted the balance of their time and energy to expanding American freedom in various ways, pushing stubbornly against the horizons of acceptable belief, thought, and practice in religion, politics, and family, all prior to and during the monumental struggle against slavery. That’s a fascinating story containing fascinating stories, so it’s all the more unfortunate that these have been unjustly eclipsed by some fan fiction about Patrick Henry and Paul Revere. Which is not to say that their generation was unimportant, of course. But their generation was not the only one!

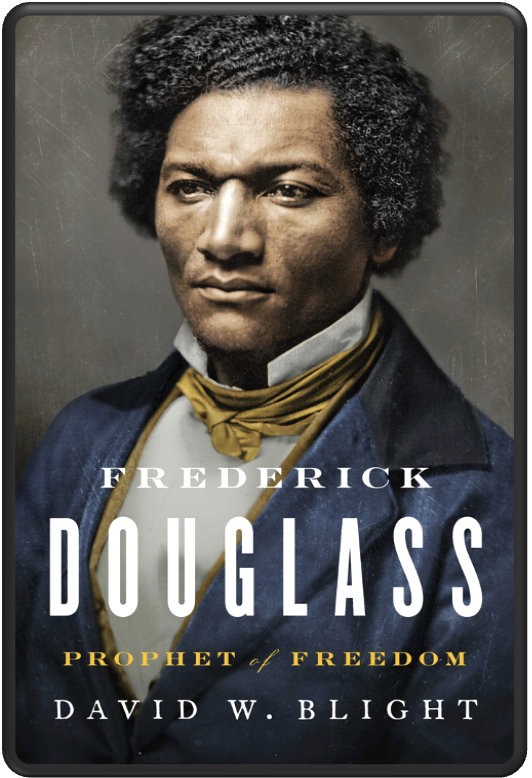

Though the Transcendentalists are personal favorites–and though this reading accompanied my first real essays on Emerson and Thoreau as well as my first visit to their homes in Concord–I found the most illuminating parts of the project in other places. Herbert Aptheker’s work on slave uprisings, though old to historians, was new to me, and the May and Burge books on Manifest Destiny and filibustering were really great. (It remains unclear to me, still, how filibuster went from “pirate” to “mercenary” to “very long speech” in American usage.) Someday I’ll read all the way through American history by way of overlapping biographies, a segment of which will take me again through Henry Mayer’s Garrison, David Blight’s Douglass, Megan Marshall’s Fuller, Robert Richardson’s Emerson, Laura Dassow Walls on Thoreau, and David S. Reynolds on Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Brown. Taken together, they’re like squares in a colorful quilt.

This fall my reading on the American past has been balanced by a separate project on degrowth economics that leans present and future. I’m wrapping that one up now, and in January will start a new list from Reconstruction through the Progressive Era. On the side I’ll be catching up on great American novels, now up through Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville. I also have a bunch of once-read volumes on Latin American history that I want to organize and revisit, but that may have to wait another year. There simply aren’t enough hours in the day or days in the month to learn all there is to learn or to understand it adequately. Trying is always, to some extent, a rewarding failure. But the books linked above offer a good start on an important era, and you may consider them recommended reading.