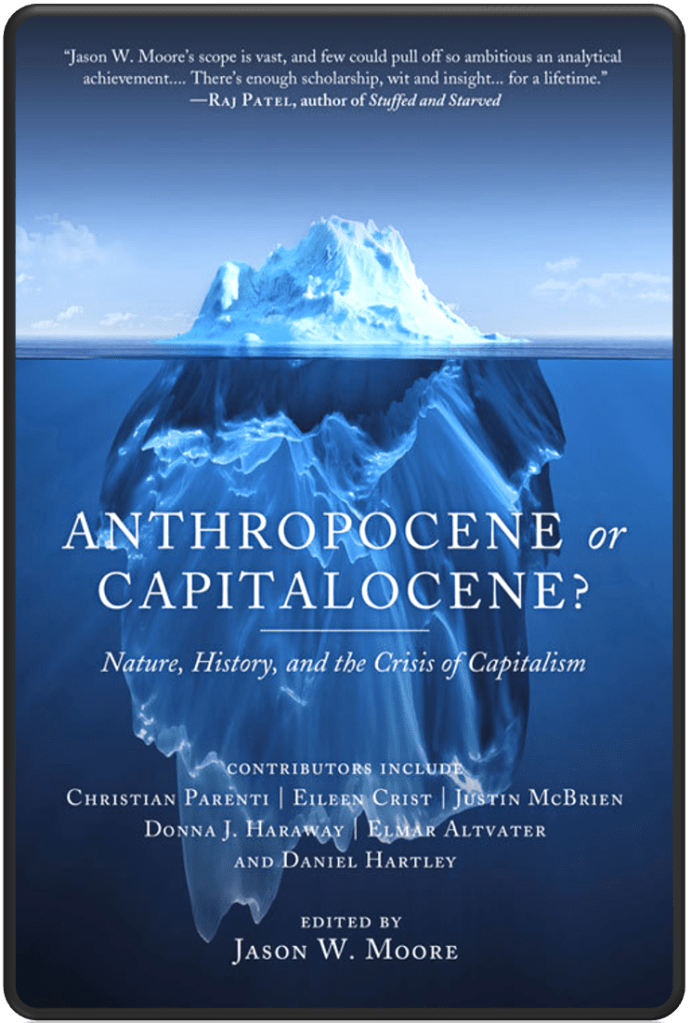

Jason W. Moore is Professor of Sociology at SUNY Binghamton, where he coordinates the World-Ecology Research Collective. His 2016 volume, Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, features essays on how the climate crisis ought to be framed and understood. Together, they argue that the dramatic changes underway are best attributed to capitalism, not to humanity as such.

For all of their explanatory power, the Anthropocene and Great Acceleration frames are not without critics, and among the most prominent are those who argue for a sharpened focus on capitalism as the historical cause and animating force of climate change and related crises. Jason W. Moore and others have suggested that the Anthropocene should be rechristened the “Capitalocene”to situate capitalism at the center of the problems. Moore and his colleagues are important to this discussion because their work has helped to orient the discourse around a web of human and extra-human relationships that they call “world ecology,” and because their arguments have informed the work of many prominent degrowth proponents.

In his contribution to Anthropocene or Capitalocene?, Daniel Hartley offers a neat, five-point summary of their critique. He notes, first, that the very term Anthropocene attributes the effects of the “human enterprise” to humanity writ large, declining to make distinctions between individuals, corporate formations, and people groups whose practices and lifestyles make them more or less culpable than others. The average American, for example, accounts for far more annual carbon emission than the average Laotian, and the average billionaire of whatever nationality contributes far more than anyone else. The ledger of responsibility therefore contains a great many rows and columns, imparting a precision and texture to the question that a blanket attribution to “humans” must necessarily obscure.

Second, both frames suggest a “purely mechanical” conception of historical causality, imagining a “one-on-one billiard ball model of technological innovation and historical effect.” Many theorists of the Anthropocene date the period to around 1800, suggesting that the invention of the steam engine inaugurated a period of more rapid growth and expansion that laid the groundwork for a Great Acceleration in the middle of the 20th century. Critics charge that such technological determinism fails to account for a wide range of older and more pervasive social, political, and economic forces that set the stage for the Industrial Revolution and its effects.

Third, the straightforward ascription of these phenomena to an easy arithmetic of humans plus technology implies a simple and certain linear progression, creating an aura of historical inevitability that forecloses on alternatives and possibilities both in the past and the future. If the catastrophic prospects looming before us now feel increasingly unavoidable, this is in part because our troublesome present has felt so inescapable, based on a review of the past that has so consistently reified a historical narrative constituted at every stage by entirely contingent parts.

Accordingly, fourth, the onward and upward trend of the human growth and development documented on the socio-economic side of the scale seems to endorse a Whig view of history defined by continual progress, with too little attention to the destructive tradeoffs along the way.

And fifth, when combined, the preceding four concerns lend themselves to “apolitical technical and managerial solutions,” suggesting that the problems inaugurated in the Anthropocene, by the earth system impacts of the Great Acceleration, may be solvable by merely technical means, like the mass deployment of solar energy projects or the geoengineering of Earth’s atmosphere. Understood holistically, however, accounting for all of its social, political, cultural, and economic facets, the great problem of our time resists our best efforts to invent our way out. It demands that we strike at the very root, recognizing this era first and foremost for its intimate entanglement with capital (154-158).

The disagreements enumerated here are often quite granular, hinging not on the direction or intensity of the established trends so much as narrower matters like their precise causes and drivers, as well as even more specialized questions about how these should be labeled and understood. But Moore argues that the answers generated will be more than merely academic:

“The difference [between Anthropocene and Capitalocene] speaks to divergent historical interpretations—and also to differences in political strategy. To locate modernity’s origins through the steam engine and the coal pit is to prioritize shutting down the steam engines and coal pits, and their twenty-first century incarnations. To locate the origins of the modern world with the rise of capitalism after 1450, with its audacious strategies of global conquest, endless commodification, and relentless rationalization, is to prioritize a much different politics—one that pursues the fundamental transformation of the relations of power, knowledge, and capital that have made the modern world. Shut down a coal plant, and you can slow global warming for a day; shut down the relations that made the coal plant, and you can stop it for good” (94).

To call our era the Capitalocene, then, is to stress that the relations that have ushered forth a global proliferation of coal plants, oil refineries, fracking pads, and other fossil fuel infrastructure have also embedded themselves deeply within our ways of thinking, acting, and being in the world—protected now by the high and ominous walls of a hegemonic discourse. Any serious attempt to break out of this restrictive condition must necessarily grapple with capitalism, its origins, its spread, its now-global reach, and the rhetorical buttresses that have secured it in place through two centuries of often fierce critique. Degrowth proponents attempt this explicitly, along the lines and timelines that Moore suggests. The question remains whether the story they tell has the rhetorical facility to reframe capitalism, shifting the popular emphasis from productivity and wealth creation onto their destructive and dangerous alter egos. But the effort is underway.

This series of posts is an effort, first, to trace out the exigencies and arguments in favor degrowth economics, as well as the contours, methods, and goals of the ideas themselves. From there it will consider some of the more articulate critiques and their counters.

Pingback: Degrowth & Its Critics #3 – Jason Hickel | Recommended Reading