Perhaps the foremost philosophical and literary figure in all of American history, Ralph Waldo Emerson is a challenging and sometimes mystifying writer. The books on this list are arranged in hope of making his life and work more accessible, and his insights somewhat more applicable to contemporary life.

In this refulgent summer, it has been a luxury to draw the breath of life.

In this refulgent summer, I’m struggling my way through a pair of essays—one on Emerson, the other on Thoreau—hopefully both to be completed and sent before classes resume in August. Writing about these characters is difficult for at least two reasons. The first challenge is that they are so deep and so layered, often so cryptic and tough to parse. Maybe the greater challenge is that so many other writers have already tackled them and said so much of what is available to say. But I think I’m overcoming both with real contributions, developed across several years of sustained readings. In Emerson’s case, I’m zeroed in on the role of intuition as a ground for truth claims, what I might call the “Emersonian Antinomian,” as it was shaped and deployed in his “Address” to the graduates of the Harvard Divinity School in 1838.

The concept of Antinomianism dates back to Martin Luther, but in America is most commonly traced to the 1630s, to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and to Anne Hutchinson, who challenged the Puritan leadership on a number of doctrinal points and who claimed direct revelation from God as the source of her authority. In that context, the rejection of particular moral strictures as evidence of sanctification is linked intimately to the matter of direct revelation—a pair of ideas that have made and continue to make religious establishments nervous. In America, and especially in the nineteenth century, the idea that God speaketh rather than spake, and that he might be dissenting from the reputable clergy, would inspire a host of enthusiastic prophets and religious movements, notably including the young Joseph Smith and his Latter-Day Saints. It would then be up to the people, in early republican fashion, to determine whether or not the revelation was credible in each case.

Emerson’s challenge to the Unitarian establishment at Harvard proposed that individuals may listen for the voice of God in their private minds, trusting their feelings and inclinations to guide them toward the truth. Though subject to caveats, the idea here is that the interior life of each human being is governed by the same system of laws that govern nature itself, and overseen in turn by the same divinity that created it. Each mind is host to its own genius that speaks in the voice of God, and may give us wisdom if we are willing to listen. (Religious establishments, like the Unitarian gatekeepers in Boston, have been understandably hesitant to cede this much influence to all comers, and recognize real opportunities for abuse.) Perhaps Emerson’s greatest contribution to Transcendentalist thought was his insistence that the intuition is real and can be trusted, empowering each of us to be truly self-reliant. That idea has since been incorporated cleanly into American common sense, yielding, among other benefits, one of my favorite Seinfeld bits.

The Divinity School Address marked the end of Emerson’s thirteen-year ministerial career, as well as the beginning of his life as an essayist and lecturer. In a sense, his professional transformation embodied the sort of change one must undergo when making the formal shift from orthodox believer to individual thinker. This is not to say, of course, that one cannot subscribe to a faith statement and be an individual with a brain. But that subscription does place some pretty rigid limits one what one is allowed to think and believe while remaining within that faith. For most religious practitioners, then and now, fidelity to the creeds was an important indicator of right thought, belief, and behavior. For Emerson, such fidelity marked deficits of courage and imagination. Over the next forty years, he pressed this idea into a variety of new venues, formalizing his thoughts and his flights into a new American literature, philosophy, and theology, while inspiring many others in and after his own generation. For that reason, if for no others, Emerson is worth engaging and trying to understand.

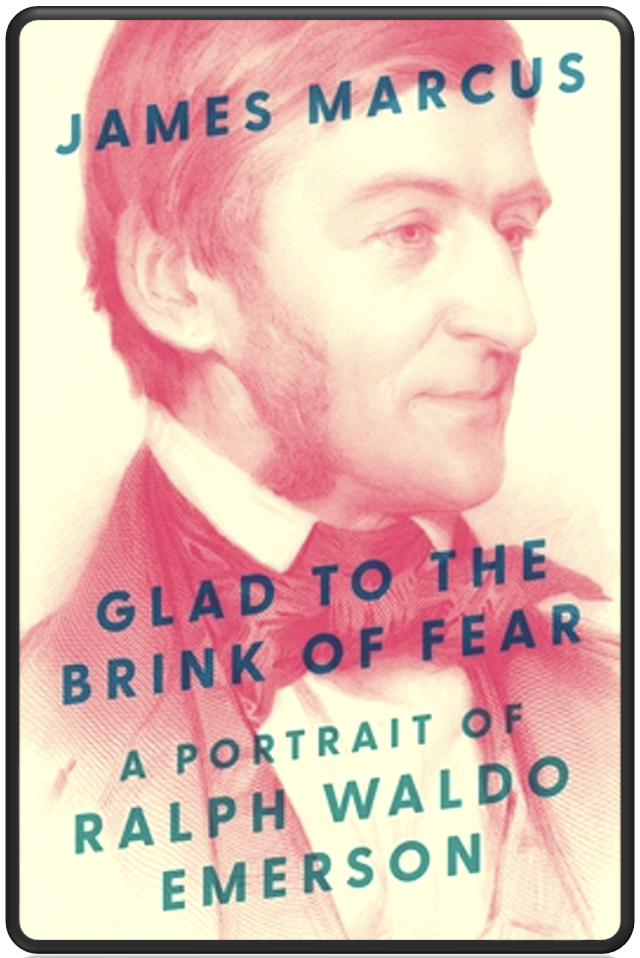

This list identifies a series of works and proposes an order to help readers acquire a foundation in one of the great men of American letters. Here again, the primary and secondary sources are interlaced, establishing Emerson’s biography before considering Nature and the early lectures, some takes on his preaching, the First and Second Series of essays, his self-reliance, selections from English Traits and Representative Men, his significance to the history of democracy and of rhetoric, and all the way up to “Conduct of Life” and some orations, including his eulogies for John Brown, Henry Thoreau, and Abraham Lincoln. Emerson’s works are all classics, as are most of the scholarly treatments included here. The most recent, James Marcus’ Glad to the Brink of Fear, will be shortly. Perhaps not featured on a great many “summer reading” schedules, these books would make welcome additions to yours.